|

the

earth-mother's

~ Pennick, Nigel, At the village of Bentham near the Yorkshire-Lancashire border, a dobbie or hobgoblin was supposed to live in a well called The Tweed Trough. On Haworth Moor, West Yorkshire, 'cat troughs' were filled with milk and honey by farmers and villagers for much the same reason that the Scottish Highlanders reputedly poured milk into their cup-and-ring stones to appease the gruagach or evil spirits or goblins/brownies. The Celtic goddess Bríde (Brigid or Bridget), associated with Imbolc (lactation) had a magical white cow, and at least one of Ireland's multiple-bullauns (Killinagh, county Leitrim) is known as St Brigid's Stone...

For a bullaun in NW England (Cumbria) click here.

|

![]()

|

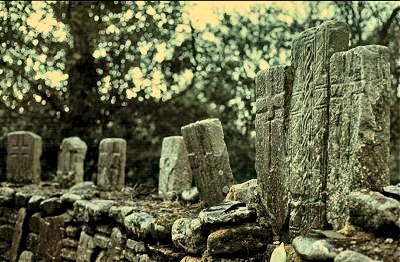

IRISH CROSS-PILLARS AND CROSS-SLABS

part two

Carrif churchyard, county Louth

Bullaun in the Glandassan River, Glendalough,

county Wicklow Kilfountan, county Kerry Toormoor or Toormour, county Sligo

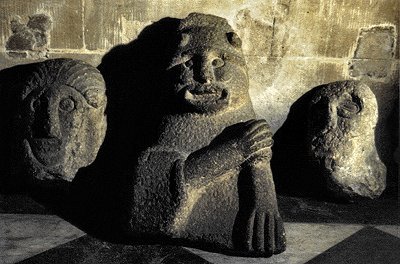

In many places all over Ireland, like Toormoor (above), remains of a monastic site have been gathered together to make a leacht or altar, beside a multiple bullaun (bottom centre). Bullauns (from a word cognate with 'bowl' and French 'bol') are usually associated with monastic sites, but their origin and function(s) are much earlier. The hemispherical depressions hollowed out of small or large boulders may have anything from one to fifteen bullauns

Triple bullaun from Ardtole church, county

Down,

Multiple-bullaun, Cong, county Mayo Multiple-bullaun, Gortavoher, county Tipperary Some

have a continuing ritual use, involving the saying of prayers

and the turning of smooth pebbles in their hemispherical beds. Multiple-bullaun, Killinagh, county Cavan The water-smoothed pebbles can occur on their own as cure-stones (or curse-stones), as on the island of Inishmurray

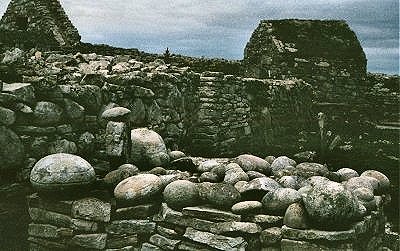

The monastic enclosure, Inishmurray, county

Sligo

Cure-stones, Killerry, county Sligo...

Deep, ringed cups and solution-pits on the

front roofstone of a Wedge-tomb

Thus some are associated with megaliths:

Templebryan North, county Cork and others look anything but Christian. Feaghna, county Kerry: multiple bullaun and phallic pebble-and-socket It is unlikely that all bullauns (of which there must have been thousands) were beds for cur[s]e-stones, and there has been some speculation as to what they contained. The story of St Kevin of Glendalough and the Deer Stone bullaun at Glendalough in county Wicklow miraculously filled with milk every morning for the saint to drink suggests a possible original use in an island which was always supremely pastoral - though the accretion of rancid curds or butter in the crevices of the stone might have been a problem. Birds would quickly have drunk milk thus left out. More likely, special grains and/or seeds might have been ground in some by a stone pestle, prior to making a ritual healing or cleansing porridge. However, in his account of the Folklore of county Clare at the end of the 19th century, T.J. Westropp told of people making hollows in front of portal-tombs and wedge-tombs, and leaving milk an offering for the Sídhe or earth-spirits - usually misleadingly translated as 'fairies'. He went on to say that stones such as that in front of the wedge-tomb at Newgrove could have been for this purpose. He names a few examples of tombs with bullauns nearby, thus suggesting that at least some bullauns (and deep cup-marks) were used for offerings of milk (a symbol of purity as well as sustenance). All somewhat speculative, of course! Another possibility is suggested by the use of bullaun-like stones in Africa, where they have been used to attract rain. A prehistoric bullaun in France has a channel in the rock leading to it, and it is reported to be almost never without water, even in very dry weather - which was when I saw it. It was large enough to have been useful as a mirror. The possibility of a more down-to-earth (additional) function cannot be excluded! Ritual they certainly were. In the graveyard (a site of evident antiquity) at Killadeas in county Fermanagh are some curious stones, including a relief carving of an ecclesiastic (The Bishop's Stone), a broken phallic pillar, a perforated stone, and a multiple-bullaun (or slab with very large cup-marks) set up on its edge and Christianised on the other side with a cross in relief.

On this Killadeas stone the

depressions could be interpreted "St Berrihert's Kyle", Ardane: always a place of poor light

Cloontuskert, county Roscommon One in county Roscommon has a combination of motifs: the 'cross-crossy' and the sacred Jewish menora. It also recalls the Icelandic End-Strife pictogram.

Poitiers (Vienne), France: The

Irish carvings have their origins, of course, in continental Europe

- and,

Grave-slab at Struell Wells, county Down. Not

all small slabs were pillow-stones. click

to The large rich, central monasteries have left us the largest number of cross-slabs, which became larger and were placed on top of the grave rather than in it. But fine grave-slabs are found in more remote spots, too.

Rossinver, county Leitrim Sometimes they were personalised with the name of the dead monk.

Fuerty, county Roscommon: the inscription

reads At Clonmacnois hundreds have been found, some of which are very elaborate, and date probably from the 11th or 12th century, whereas others might be four or five hundred years older. Clonmacnois, county Offaly

Dalkey, county Dublin On the other hand, a grave-slab in county Cork shows a more urbane influence, possibly from Britain or Continental Europe, with its sophisticated 45° labyrinth pattern.

Tullylease, county Cork - the Latin incription

reads: The distinction between cross-slabs and cross-pillars is blurred. Some larger slabs have subsequently been erected as pillars. And some fallen cross-pillars look like slabs... _____________top of page______________

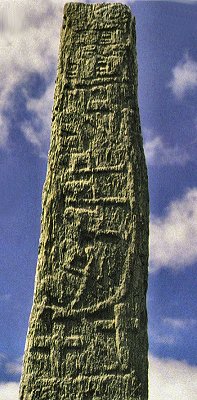

On the island of Inishmurray, off the coast of Sligo, many cross-slabs and pillars survive, as well as ruined churches and monks' cells (known as clocháns). Some slabs and pillars have been set up on leachta, others stood or lay about until recently removed to the schoolhouse 'for their protection'.

A

panoramic virtual visit to the island, with an excellent essay

on its history, can be enjoyed at

The same combination of rectilinear with curvilinear design occurs on grave-slabs. One such, carved on both sides is one of a few known to have crossed and re-crossed the Atlantic as talismans to help the afflicted descendants of emigrants from the area.

Bruckless, county Donegal: two sides of the same slab.

The eighth 'station' at Glencolumbcille.

Inishbofin, co. Galway

Caher Island, co. Mayo

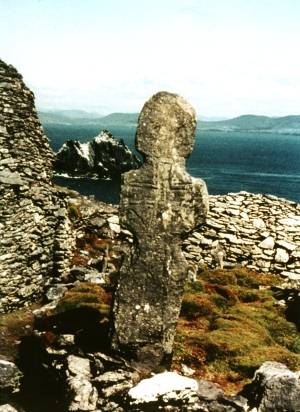

On the island of Inishkea North, large cross-slabs (unlikely to be funerary) become crucifixion-slabs.

Inishkea North, county Mayo: click

for a larger picture

Tullaghora, county Antrim

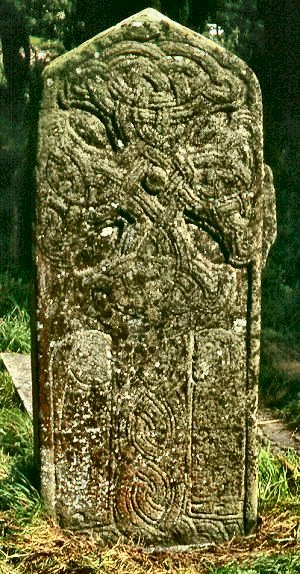

Legananny, county Down and, more spectacularly, at Skellig Michael, county Kerry. In rich inland monasteries, by the Romanesque period, carving of small slabs was as sophisticated as that of the 'Scripture Crosses', with truly Romanesque motifs such as sinners being devoured and strangled by the Serpent.

Gallen, county Offaly Another development was the "face-cross", on much smaller slabs or very small pillars.

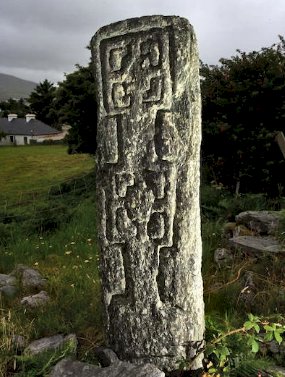

Knappaghmanagh, county Mayo: This little pillar, in a still-used ancient graveyard, is of the simpler, more primitive kind.

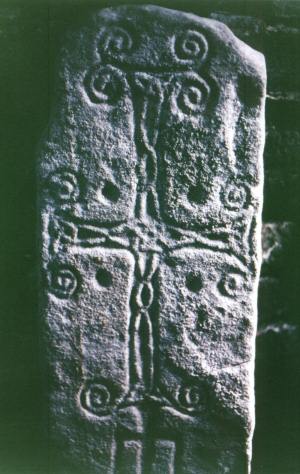

Kilbroney, county Down. It is in the north-west county of Donegal that pillars, slabs and crucifixions merge together, and associate with motifs drawn both from pre-Christian Ireland and Merovingian France.

Fahan Mura, county Donegal

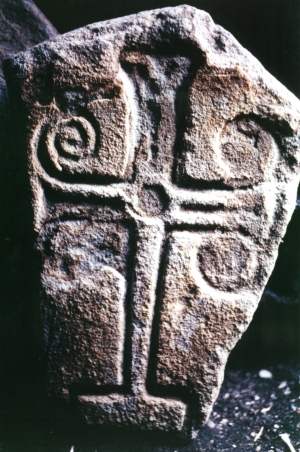

Cross-pillar, Carndonagh, county Donegal Inishkeel, county Donegal Drumhallagh, county Donegal: Knots

and circular motifs of various kinds become a common feature on

the sculptured crosses of the following centuries - along with

enigmatic human figures,

as well as Biblical scenes such as The Fall, Cain and Abel, King

David playing his harp, Daniel in the Lions' Den, the Baptism

of Jesus, and the Last Supper.

Cross and "guard-pillars", Carndonagh,

county Donegal;

"Guard-pillar" of the cross at

Carndonagh, county Donegal: Manticora on the side of a cross-pillar

(or cross-shaft) Click on the picture to read |

closer view

closer view