|

the

earth-mother's

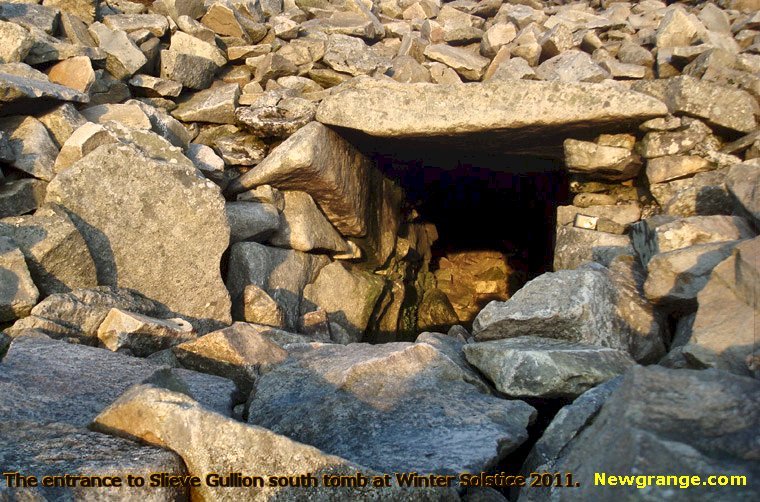

HOW TO IDENTIFY PASSAGE-TOMBS

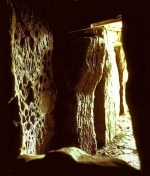

Passage-tombs are identified principally by their passages, which can be from one to ten metres long. Some, in the NE of Ireland, however, can look like small portal-tombs - but, of course, don't have the distinctive portal-stones. Their cairns are always circular, and sometimes only the kerb - or nothing at all - survives.

from "The Sunday Telegraph", London, 10th August, 2003: by

The Druids have put up huge roadside monoliths to restore the natural flow of "earth energy". After the massive pillars of white quartz were put up beside a notorious stretch of road during a secret two-year trial, the number of fatal accidents fell from an average of six a year to zero. Gerald Knobloch, who describes himself as an archdruid, used a divining rod to inspect the 300-yard stretch of the A9 in Styria and restore "earth energy lines". "I located dangerous elements that had disrupted the energy flow," he told The Telegraph. "The worst was a river which human interference had forced to flow against its natural direction. By erecting two stones of quartz each weighing more than a ton at the side of the road the energy lines were restored." The pillars had a similar function to acupuncture, he said. "Acupuncture needles also restore broken energy lines. What acupuncture does for the body, the stones do for the environment." Harald Dirnbacher, an engineer from the motorway authority, admitted that they turned to Mr Knobloch as a last resort. "We had put up signs to reduce speed, renewed the road surface and made bends more secure but we still kept getting accidents," he said. "At that point we couldn't think of anything else to do and decided we might as well try anything. "I admit when we first looked at it [energy lines] we were doubtful. We didn't want people to know in case they laughed at us, so we kept the trial secret and small-scale. But it was really an amazing turn-around." Scientists are sceptical of the claims. "Natural sciences need evidence. Whatever can't be measured, does not exist," said Dr Georg Walach, a geophysics professor at Leoben University in southern Austria. "These energy lines and their flow cannot be grasped or measured, and their existence is therefore rejected by scientists." However, the motorway authorities are extending the Druids' role across the country, paying them about £2,500 (Euro 3,500) for each investigation - a fraction of the cost of resurfacing a road. "Of course, the fall in accidents could be due to something else, as we are continuously repairing the roads," said Mr Dirnbacher. _______

Quartz is especially associated with rock-art sites in North America.

|

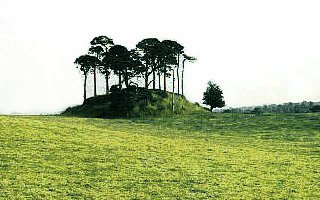

A typical tree-grown tumulus containing a small, lowland passage-tomb.

|

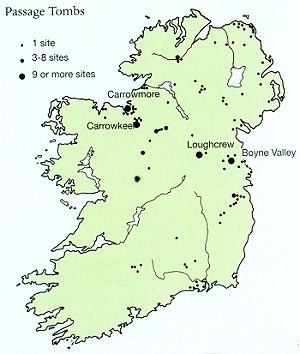

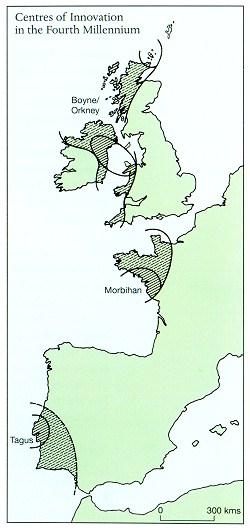

Passage-tombs derive from the simple 'boulder-circles' of Carrowmore, ancestors of all the Stone circles of Atlantic Europe, which enclosed simple small boulder-built chambers.

These structures

- the earliest known buildings in Europe - were built over

seven thousand years ago near what is now Sligo town: not

quite the easternmost point of the west coast of the Land of the

Setting sun. Occupying the edge of the little Carrowmore plateau,

they mostly align towards a 'ritual centre', and were 'intimate

megaliths' not built to impress or be seen from afar. They have been interpreted as quiet sacred places - rather like modern parish churches (which have far more burials than any prehistoric mound, yet are not thought of as primarily sepulchral) - erected by a fairly egalitarian society which lived close by, on especially-good land with a climate favoured (rather than battered) by the sea, which was also, of course, the main highway until late mediæval times. This might have been a matriarchal, ancestor-worshipping society which inevitably made the mistake of allowing boys to form secret societies and play with big stones - and big clubs. Later on, tombs with high visibility and prestige were built away from Carrowmore on the Slieve Gamph or Ox Mountains to the south-west. Some of them had more complex cruciform chambers and large cairns. The dead were now distanced and elevated from a more stratified society with a labouring class, and the shrine-houses of the dead no longer fitted into the landscape, but dominated it. The third phase is represented by the huge cairns of Misgán Méadbha on Knocknarea, and Listoghil in Carrowmore - perhaps built later than their burial-chambers. These complex monuments required huge labour-resources, and must have been built by a fairly totalitarian society. Later still, the highly visible hilltop cairns on Carrowkeel, all supervised by the all-seeing and probably baleful eye of Misgán Méadbha, were built as a kind of new necropolitan annexe to the already venerable sacred area of Carrowmore. At the same time, the passages tended to get longer, and the chambers acquired recesses marked by sills. None of these temple-tombs-built-to-impress was decorated with what has come to be regarded as 'Passage-tomb Art'. It was when the highly visible hilltop tombs of Loughcrew were constructed that significant stones in the recesses or close to the chamber acquired the symbolic designs so typical of passage-tomb 'art'.

...and occasionally on low ground.

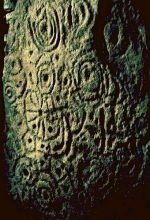

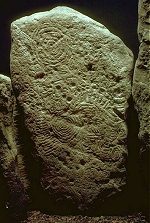

And as they moved south-eastwards towards the Isles of Scilly off Cornwall, the passage and the chamber became a single space, undivided by stone though possibly by curtain or wattle screen. There were evidently violent clashes between cultures and groups, as shown by the complex site of Baltinglass Hill in Wicklow, where a passage-tomb was overlaid and partly-destroyed by the kerb of another, which was in turn succeeded by a simpler tomb than the previous two. By the time the central, triumphalist passage-tomb-building societies had extended their activities and influence from Sligo, via the skyline-necropolises of Carrowkeel and Loughcrew, as far as the Bend of the Boyne - where (apart from the absence of dominating heights) the land and landscape resembled the 'Sacred Plateau' of Carrowmore and environs - they had become obsessed, like the Babylonians whose systems we still use, with astronomy and astrology, and obviously were a plutocratic, totalitarian hierocracy. Much has admiringly been written about the alignments, azimuths, nadirs, orientations and occidentations of the Bend of the Boyne monuments (some of them more like totalitarian palaces of culture and science than tombs), but this web-page will not attempt to enter such arcane discussion, since it is more concerned with stone monuments in landscape than astronomy and astrology. Suffice to say, light enters the passages of very many tombs and strikes

significant stones at sunrise on solstice, equinox or quarter-days.

Lines of suns depicted on stones may follow the sun's

path through the ecliptic, while crescents and wavy lines seem to

record lunar trajectories. These huge, labour-costly, vainglorious monuments and their suburban satellites were, like the Egyptian pyramids, built to impress and dominate all who saw them, and were guarantees of hierarchical life after death (no afterlife is egalitarian), as well as solar, lunar and bright-star observatories. The impressive engravings related to the cycle of life, death, the seasons and the after-death journey to or in the Otherworld(s) - a journey which was certainly seen as cosmic. Many of the engraved stones look like star-maps - or dream-maps: the two are not mutually-exclusive. In any event, they are certainly power-maps. (It is interesting to speculate, however, on the influence of Lichens on passage-tomb and boulder engraving.)

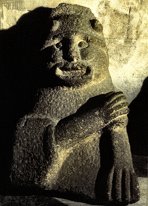

Some have cartouches on them, not unlike those of the Egyptian tomb-paintings.

Others have anthropomorphic designs on them, whereas yet others

have simple symbolic decoration such as zig-zags, lozenges, meanders

and concentric circles - or combinations of such motifs.

Whether used for divination, making spells, astrology, astronomy, genealogy or story-telling - or any combination - the carefully-pecked 'art' of the passage-tombs is undoubtedly lithomantic. They may be spirit-traps, or messages to the spirit-world. They may be dream-maps, maybe records of induced hallucinations. Or they may be symbol-doodles meaningful only to the doodler or his small group. In recent times people have wished necromancy and human sacrifice on to the passage-tomb builders. Who is to know precisely what combination of necromantic practices, funeral ritual, magic, prognostication and even astronomical-meteorological record were carried out in these remarkable edifices ? Recently a theory has been proposed that some are actual topographical maps of monuments, though why they would be 'written in stone' rather than on wood - or indeed at all - is not explained. Read the (badly-written) PDF on Tara and on the Bend of the Boyne.

These petroglyphs

or rock-scribings (or rock-art), generally assigned

to the Bronze Age, may share at least some functions and concerns

with the art of the Neolithic passage-tombs. They may be purely

derivative, or they may represent an independent (though obviously

related) tradition of lithomancy. Their distribution near the coast

at different altitudes recalls the littoral origin of passage-tomb

construction, and their function is perhaps more mysterious, if

less varied.

|

'Sampler' Rugs by Anthony Weir featuring various motifs from passage-tombs.

Click on the thumbnails

for high-resolution pictures.

enlarge

enlarge