|

petroglyphs

the

earth-mother's

|

|

IRISH

PREHISTORIC ARCHITECTURE

Maps or magic ?

|

|

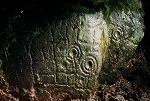

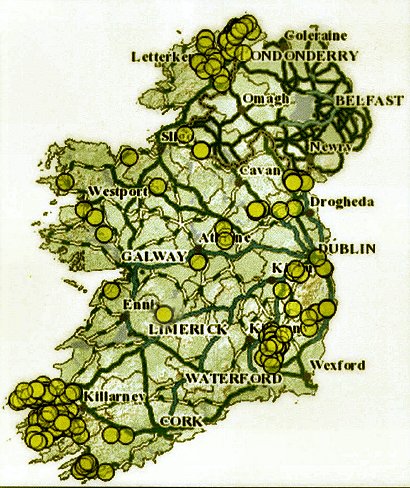

These petroglyphs or rock-scribings (or rock-art), generally assigned to the Bronze Age, may share at least some functions and concerns with the art of the Neolithic passage-tombs. They may be purely derivative, or they may represent an independent (though obviously related) tradition of lithomancy. Their distribution around the coastline at different altitudes recalls the littoral origin of passage-tombs, and their function is perhaps more mysterious, if less varied. While littoral rock-scribings on La Palma in the Canary Islands are very similar to Breton and Irish passage-tomb designs (particularly those at Sess Kilgreen in Tyrone), they and the Irish petroglyphs are very different from the petroglyphs of southern Sweden and Norway representing ithyphallic hunters, game, sun-wheels and boats (see right). Some of the Irish and British petroglyphs more resemble pictographs such as the traffic-signs and concourse-notices that occur everywhere today. They are also unrelated to the crude criss-cross patterns found very occasionally at or in court-, portal- and wedge-tombs... ...and, in one instance, on a rock face. But they are obviously related to the cup-marks which evolved from natural solution-pits in rock and boulders, and which were sometimes enhanced by surrounding rings.

They are never extensive like some in Argyll which cover up to 1800 square metres. Like the other Atlantic petroglyphs they are mostly on horizontal outcrops or on table-like surfaces of boulders. They were originally painted with earth and charcoal colours: ochre, red and black - as might have been the passage-tomb engravings, too. And like the far more numerous stone circles, they are nearly always carved where there is a panorama or a wide open view. One exception occurs in county Kerry, which has the highest concentration of Irish petroglyphs. Another occurs in the other county of high petroglyphic concentration: Donegal. They also occur on the vertical surfaces of standing-stones which are the principal or marker stones of alignments. But petroglyphs are not obviously"cultic" like the relatively easy-to-interpret stones of the Iron Age - of which our culture is a hugely-enhanced extension. The most frequent motif is the cup-and-ring, or cup and partial ring (sometimes with a tail which always points downwards) and surfaces with this motif tend to occur near places where copper or gold ores were mined. Hence the possibility that they are priestly-prospectors' maps or signposts. (A famous carved rock face at Valcamonica in N Lombardy - nowhere near the sea - is thought to be a map showing buildings, streams, paths and fields.) One site at least has sun-viewing significance twice a year, so this also must be reckoned with. Other petroglyphic motifs, such as the multiple concentric ring and the multiple concentric lozenge which occur frequently in passage-tombs, have been found on the lower surfaces of the covers of kist-tombs - which sometimes have come from elsewhere and re-used or adapted for funerary use.

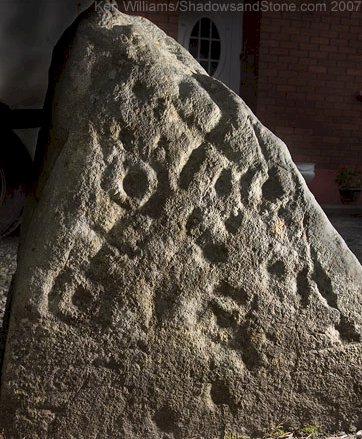

It is now thought that the earliest, most 'primitive' petroglyphs: patterns of dots (cupmarks), sun-bursts, grid-patterns, spirals, zig-zags, snake-forms and wavy lines, are phosphenic or entoptic: i.e. they are influenced by the 'visions' we get when we rub our eyes briskly and keep them shut, or when hallucinating. Such designs occur all over the world, and in both passage-tomb and rock-surface designs in Ireland. More complicated designs are usually developments of these phosphenic 'elements'. But, of course, as I mentioned above, patterns of dots, in the form of solution-pits, occur naturally in rock. Certainly they had a 'mystic' and 'ritual' significance which fitted in with funeral rites, early astronomy and metal-mining. They are also part of a common Atlantic seaboard (or edge-of-the-known-world) culture which persists today in the striking similarities of character in people inhabiting a littoral line passing from Norway around Scotland and Ireland, across to Cornwall and over to Brittany, across the Bay of Biscay to Asturias and Portugalicia, and on to the Canary Islands off the Moroccan coast. Petroglyphs of probably-similar date also occur at least as far south as Gabon. A connection with bullauns is likely. And if bullaun-like stones in Africa have been used to attract rain, then, in the Irish climate which deteriorated so much in the Early Bronze Age, both cup-marks and bullauns could have been attempts to attract the sun. But their interest lies mainly in their appeal and surprise to the eye. In an island where you might have to drive at least ten miles to find something beautiful made by man (unlike many parts of rural Europe where you have to drive at least ten miles to find an ugly building), petroglyphic rocks and stones are especially delightful - even if, like the one pictured above, it was irreverently dumped at the edge of a field and lost for several years, before being placed in a private backyard.

|

|

back to |

|

Psychoacoustic influences of the echoing environments of prehistoric art by Steven J. Waller, Ph.D. Cave paintings and ancient petroglyphs around the world are typically found in echo-rich locations such as caves, canyons, and rocky cliff faces. Analysis of field data shows that echo decibel levels at a large number of prehistoric art sites are higher than those at non-decorated locations. The selection of these echoing environments by the artists appears not to be a mere coincidence. This paper considers the perception of an echoed sound as a psychoacoustic event that would have been inexplicable to ancient humans. A variety of ancient legends from cultures on several continents attribute the phenomenon of echoes to supernatural beings. These legends, together with the quantitative data, strongly implicate echoing as relevant to the artists of the past. The notion that the echoes were caused by spirits within the rock would explain not only the unusual locations of prehistoric art, but also the perplexing subject matter. For example, the common theme of hoofed animal imagery could have been inspired by echoes of percussion noises perceived as hoof beats. Further systematic acoustical studies of prehistoric art sites is warranted. Conservation of the natural acoustic properties of rock art environments - a previously unrecognized need - is urged. A new area for acoustic research has arisen from a previously unsuspected relationship between ancient legends of echoes, and prehistoric art. Could echoes have been a motivational influence for the ancient artists? Acoustic studies at archaeological sites may be starting to answer this important question. To illustrate the universal perception of echoes being attributed to a supernatural phenomenon in the ancient world, some examples of ethnographically-recorded legends are listed below: - The classical Greeks numbered among their deities a nymph called Echo (Bonnefoy 1992). - From the South Pacific: “Echo as the bodiless voice, is the earliest of all existence” (Jobes 1961:490). - A Paiute legend states that "witches have lived in snakeskins and hidden among rocks, from which they take great delight in repeating the words of passersby." (Gill and Sullivan 1992:79). - The Book of the Hopi describes the importance of a mythological being named Echo in the creation story (Williamson 1984). Based on documented legends that echoes were considered to be caused by spirits, it is theorized (Waller 1993a,b) that sound reflecting locations were perceived as the dwelling places of these echoing spirits. Special echoing places - such as caves, canyons, rock shelters, cliffs and stony mountainsides - where spirits dwelt and audibly responded to mortals would undoubtedly have been considered sacred sites. It would not be surprising then to find evidence that ritualistic activities had been conducted at such sacred echoing sites around the world, and had been decorated by the artists of those ancient cultures. Has archaeological evidence of homage been found in these types of echoing locations? The answer is a resounding “YES!”. There are hundreds of Paleolithic caves in Europe with prehistoric paintings and engravings deep within. In Africa and Australia there are thousands of painted rock shelters. In America the canyons of the Southwest contain thousands upon thousands of ancient petroglyphs and pictographs. See Figure 1 for an example of rock art in the form of mysterious petroglyphs.

|

Click

the picture below for sites specially visited and photographed by

Ken Williams.

Click on the thumbnails

for high-resolution pictures.