|

the

earth-mother's

HOW TO IDENTIFY WEDGE-TOMBS

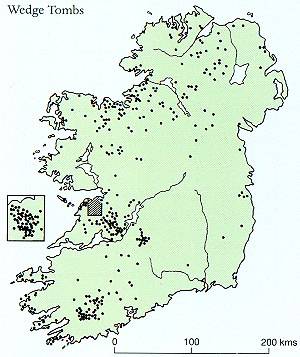

Wedge-tombs almost always face South-west, are wedge-shaped in plan and elevation, and have double-walling along both sides of their gallery, which is much shorter than that of most court-tombs, and rather longer than that of portal-tombs. The front part of the gallery is divided by a low septal slab (like a high threshold) to form a portico or antechamber. The cairns, where they survive, tend to be smaller than those of court-tombs. Their distribution tends to be concentrated more in the south and west than that of court- or portal-tombs.

|

text and photographs

by Anthony Weir

|

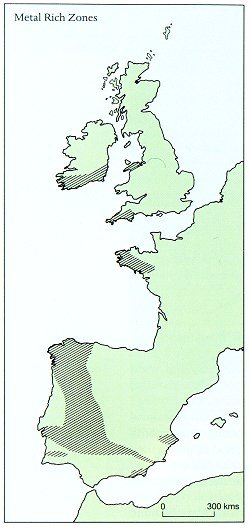

Many of these tombs resemble to some extent the squat dolmens-simples of France, though they rarely are quite so simple. Wedge-tombs in the west of Ireland, especially in the little limestone karst or causse of The Burren, are box-shaped, and like all Irish wedge-tombs have distinctive close double-walling of the gallery: a feature found in a few French tombs. As with French tombs, and even more than Irish portal-tombs, chocking-stones were often used to make the roof-stone(s) steady. The burial chamber is often entered through a small antechamber or portico, from which it is divided by a septal slab or large sill-stone. Those wedge-tombs which are not box-like (the majority) tend to be D-shaped, with straight façade of matched orthostats and a tapering or heel-shaped chamber behind it. The cairn also tends to be D-shaped. Wedge-tombs, built a little later than Portal-tombs, are associated with people who had the techniques for smelting copper and tin and making bronze. Thus, as the climate deteriorated to more or less its present chilliness, they needed to and were able to cut down more trees and work previously-intractable (heavier) and inaccessible land - a process which has gathered pace across the millennia, so that Ireland is now the least-forested country in Europe. (More recently, trees have been felled merely to winter-feed cattle with the ivy growing upon them!) Their distribution stretches across the uplands of the whole island including the south and west, where very few earlier tombs were built. Those in the north-east of Ireland tend to be fairly elaborate, and feature a double or divided entrance created by the insertion of an orthostat in the entrance to the portico. A handful

are highly reminiscent of the long gallery-tombs or alleés-couvertes

of France. But most are modest, almost homely, structures. Some feature apertures through which a soul might escape or ritual food be offered. The period of their construction coincided both with deterioration of the climate and the overgrazing that we see today - which turned the fertile and well-drained lower uplands to blanket-bog: yet another human Land of Lost Content. Many wedge-tombs, like most of the stone circles and rows that were built around the same time or later - and unlike the tombs which preceded them - tend to face the winter or summer sunset: the souls of the departed, perhaps, could fly out through the door and follow it, persuade it to return (or, on the other hand, continue) in its former warm and life-enhancing splendour. On the other hand, he entrances of many of the Munster (Cork & Kerry) tombs face towards the settings of the major and minor southern moons. A terrible fear of Bronze-age people in Northern Europe must have been that the climate would keep on deteriorating, and that one day the sun simply would not rise. And, perhaps, that the sun was rising only by human inducement through prayer, ritual and the orientation of architecture. When there are examples of so many tombs, we should remember that each one (like each modern school) was different, and built by separate groups or communities of people. There is unlikely to have been one single cult or belief-system or even cosmology. Moreover, we must distinguish between the builders' intentions and the uses to which the tombs were put by later generations or incoming people- like, for example, 19th century National Schools today, some of which are private homes, while others are craft-boutiques. As for the enigma of the double-walling, so similar to modern cavity-construction - the mystery remains. _________________________________________________

|

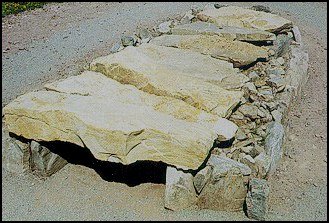

Modern simulation of a rather low wedge-tomb at Creggan folk-park,

Omagh, county Tyrone.

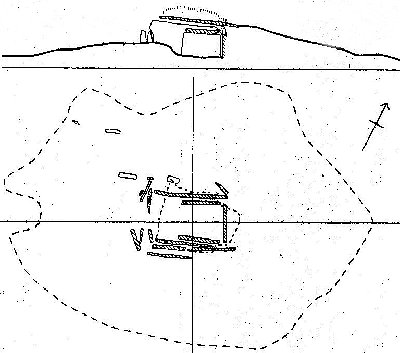

Profile and plan of a typical Burren wedge tomb at Baur South.

"The

past is not over - it has not even passed."

William

Faulkner

In his account of the Folklore of county Clare at the end of the 19th century, T.J. Westropp told of people making hollows in front of portal-tombs and wedge-tombs, and leaving milk an offering for the Sídhe or earth-spirits - usually misleadingly translated as 'fairies'. He goes on to say that stones such as that in front of the wedge-tomb at Newgrove could have been for this purpose. He names a few examples of tombs with bullauns nearby, thus suggesting that at least some bullauns (and deep cup-marks) were used for offerings of milk. (- All somewhat speculative, of course!) |

recommended reading:

O'Brien, Billy:

Sacred Ground: Bronze Age Studies 4

Department of Archæology, National University of Ireland, Galway, 1999

ISBN 0 9535620 0 X - paperback, £25

For maps of tombs and stone circles in Ulster (six counties) peatlands see:

www.peatlandsni.gov.uk/archaeology/tombs.htm#stonecirclesmap

Click on the

thumbnails

to see large

high-

resolution

pictures.